What appeared to be a simple cave concealed the history of a forgotten human lineage

Your genome carries quiet traces of meetings your ancestors once had with other kinds of humans. Some of those traces come from the Denisovans, a population that science met first in DNA, then slowly in bone.

A new wave of research is turning these strangers into neighbors by stitching together where they lived, when they thrived, and what they left behind in people today.

The work draws on cave sediments, ancient proteins, and high resolution timelines to replace mystery with detail.

Zenobia Jacobs, University of Wollongong, and an international team are among the scientists leading this effort. Their latest results map a full history of Denisova Cave across hundreds of thousands of years.

DNA in the Denisovan cave

In 2010, researchers extracted mitochondrial DNA from a tiny finger bone in Denisova Cave and realized it did not match modern humans or Neanderthals, introducing a previously unknown hominin lineage.

That first genome built the case for a population that had been invisible to the fossil record.

Follow up nuclear DNA work showed Denisovans and Neanderthals were sister groups and, crucially, that ancestors of people from Melanesia carry Denisovan ancestry.

Those findings suggested that it contributed 4-6% of its genetic material to the genomes of present-day Melanesians.

High places, thin air

Clues soon appeared far from Siberia. In 2019, proteins extracted from the Xiahe mandible found in Baishiya Karst Cave on the Tibetan Plateau tied that jaw to Denisovans, placing them at high altitude roughly 160,000 years ago.

The fossil filled a geographic and ecological gap. Genetics in living people already hinted at this story.

A 2014 study showed that a Tibetan haplotype for low oxygen adaptation can only be convincingly explained by introgression of DNA from Denisovan or Denisovan related individuals into humans.

That is one practical way the Denisovans still matter in human health today.

Family with many branches

The Denisovan trail is uneven. Some fossils are sparse, and some identifications remain debated.

In 2021, a large skull from Harbin, China, was described as species Homo longi, a proposed species whose traits differ from both Neanderthals and modern humans. The specimen’s story is still unfolding.

Fresh analyses are testing whether such East Asian fossils could represent Denisovan populations scattered beyond Siberia. That debate is sharpening how researchers read teeth and skulls against genomes and proteins.

Sediment stories in Denisova Cave

The newest advance is not a spectacular skull but the steady accumulation of DNA. and precise optical dating.

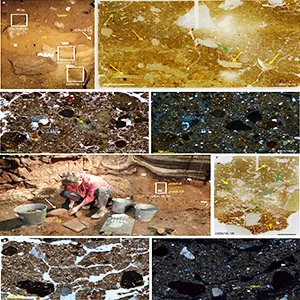

Jacobs and colleagues combined 150 new ages with genetic data from all three chambers of Denisova Cave and analyzed 963 sediment samples to reconstruct a whole cave timeline across the last 300,000 years, substantially enlarging the record of Denisovan presence after 80,000 years ago.

Their integrated chronology links shifts in hominin DNA with environmental and faunal changes through time.

The same cave yielded a one of a kind individual: Denisova 11, the daughter of a Neanderthal mother and a Denisovan father. That single life shows contact was not just theoretical, it was personal.

Fossils off the beaten path

Evidence for Denisovans did not all come from caves. A robust lower jaw dredged near Taiwan, published in 2015, shows archaic features that some researchers compare with Denisovan-like teeth, expanding the possible range of late hominin diversity in East Asia.

A lone tooth from northern Laos, described in 2022, resembles Denisovan molars and places a Denisovan like signal in Southeast Asia’s tropics. These finds add breadth to an otherwise DNA heavy picture.

A complementary technique lifted the approach beyond bones.

A 2021 study showed how dense grids of sediment sampling can reveal occupation pulses by Denisovans, Neanderthals, and later modern humans, even when no skeletal remains survive. This method is now central to turning scattered traces into lifelike timelines.

Genetic echoes in living people

Denisovan DNA is not a museum piece, it is a living inheritance. A 2021 study reported that the Ayta Magbukon people in the Philippines “possess the highest level of Denisovan ancestry in the world.”

Denisovan ancestry is also widespread in parts of Island Southeast Asia and New Guinea.

Multiple episodes of Denisovan gene flow into different human groups now look likely.

Analyses of modern genomes point to more than one Denisovan population contributing DNA across Asia, which matches the geographic scatter hinted at by fossils and cave sediments.

Those echoes help researchers follow population movements and contacts that left only thin archaeological footprints.

Why the Denisova cave matters

Denisovans force us to rethink labels. They were close kin to Neanderthals yet adapted to high altitudes, present in cold Siberia and warm Southeast Asia, and contributors of useful traits to our species.

Those facts point to a flexible, resilient people who met and sometimes mixed with others in a changing Pleistocene world.

They also show how methods change what we can know.

DNA captured from soil, proteins preserved in mineral crusts, and calendar year chronologies let researchers track hominin populations through layers and climate swings, not just dates on a chart.

That is how a “ghost population” becomes part of a human story that is still being written.

The study is published in Nature Communications.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–