Human ancestors hiked many miles to get special materials they liked for making stone tools

In the hills of southwestern Kenya, more than 2.6 million years ago, early hominins were doing more than just surviving – they were planning ahead. They used sharp-edged stone tools to process plants and butcher massive prey like hippos.

But what’s more surprising is this: they hauled the raw materials for those tools from over six miles away. That detail changes what we thought we knew about the beginnings of tool use.

Early hominins went the distance

A team of researchers from the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, the Cleveland Museum of Natural History, and Queens College found evidence that ancient hominins on Kenya’s Homa Peninsula sourced specific kinds of stone from distant locations.

The study pushes back the earliest known evidence of long-distance transport of toolmaking materials by a staggering 600,000 years.

“People often focus on the tools themselves, but the real innovation of the Oldowan may actually be the transport of resources from one place to another,” said Rick Potts, senior author of the study.

“The knowledge and intent to bring stone material to rich food sources was apparently an integral part of toolmaking behavior at the outset of the Oldowan.”

Nyayanga reveals ancient behavior

The researchers focused on an area called Nyayanga, on the Homa Peninsula, near the shores of Lake Victoria. The region is rich in fossils and has been the subject of decades of fieldwork.

Potts began surveying the area in 1985 and later partnered with colleagues from the National Museums of Kenya. The work is part of the ongoing Homa Peninsula Paleoanthropology Project, which is co-directed with Queens College professor Thomas Plummer.

Emma Finestone of the Cleveland Museum of Natural History joined the project in 2012. She and the team have since been piecing together how ancient hominins moved across the landscape and used stone tools to interact with their environment.

Early tools cut hippos

At Nyayanga, they uncovered a cache of stone tools and hundreds of butchered hippopotamus bones, some of which dated back nearly three million years. In a 2023 study, the same team proposed that these remains may represent the earliest known example of stone tools used to butcher large animals.

“Hominins were using stone tools for a variety of pounding and cutting tasks, including processing plant and animal foods, and working wood,” said Plummer.

“The diversity of activities that used stone tools suggests that even at this early stage of cultural development stone tools enhanced the adaptability of the hominins using them.”

The first stone tools

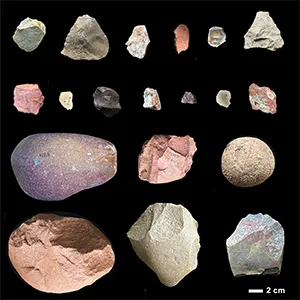

The toolkit in question is known as the Oldowan. It’s a collection of basic but effective tools: hammerstones, sharp flakes, and stone cores.

With these, early humans could smash bones, slice meat, and process plant material more efficiently than with bare hands or teeth.

These stone tools weren’t just random rocks picked up off the ground. The stone had to be tough yet brittle enough to break into sharp edges.

That’s where the mystery deepened. Nyayanga’s local rock is too soft to be useful for long; any tool made from it would dull quickly or crumble under pressure.

So, where did the stone for the tools come from? To find out, the team analyzed the chemical makeup of hundreds of stone flakes and cores.

The researchers found that most were made from rhyolite and quartzite – types of stone not found locally. The nearest sources of these rock types are located in riverbeds more than six miles to the east.

Early hominins planned ahead

Many animals use tools. Some, like chimpanzees, even carry them short distances. But these early hominins went farther.

They knew where to find the best material and how to get it back to a location that was rich in food. That shows not just physical ability but cognitive planning.

“The mental maps of the oldest known hominins to persistently make stone tools well surpassed their immediate surroundings, even surpassing a few miles,” said Potts.

The hominins weren’t just reacting to their environment. They were thinking ahead – remembering locations, assessing needs, and choosing the right time to act.

Fossils hint at makers

One big question remains: which ancient species made these tools? At the Nyayanga site, researchers found a molar tooth belonging to a hominin in the genus Paranthropus, known for its powerful jaws and grinding teeth.

Researchers found another Paranthropus tooth on the surface nearby. These fossils suggest the hominins may have made the tools – or at least were present when others used them.

“Unless you find a hominin fossil actually holding a tool, you won’t be able to say definitively which species are making which stone tool assemblages,” Finestone said. “The research at Nyayanga suggests that there is a greater diversity of hominins making early stone tools than previously thought.”

A long tradition of tool use

This discovery adds a deeper layer to our understanding of hominin behavior. Early hominins weren’t just scraping by. They were problem-solvers, strategists, and mobile toolmakers.

“Humans have always relied on tools to solve adaptive challenges,” said Finestone. “By understanding how this relationship began, we can better see our connection to it today – especially as we face new challenges in a world shaped by technology.”

The full study was published in the journal Science Advances.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–