Primitive human population discovered that had no contact with the rest of the world

Some of our ancestors were much more adventurous than we have given them credit for. A new study describes how hunter gatherers were crossing the the Mediterranean to reach the island of Malta about 8,500 years ago, centuries before farming communities appeared on the islands.

The team uncovered a compact record of life on a small island: hearths stacked in ash, simple stone flakes, and cooked animal remains inside a cave called Latnija in northern Mellieħa. Those layers push Malta’s human story back by about a millennium.

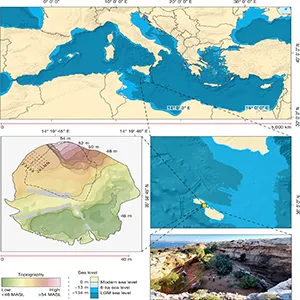

Crossing the sea to reach Malta

The research was led by Professor Eleanor Scerri at the Max Planck Institute of Geoanthropology (MPG) and the University of Malta, with colleagues.

Their work outlines a Mesolithic presence on Malta that lasted until roughly 7,500 years ago, right before the Neolithic took hold across the region.

Radiocarbon dates from charcoal and edible shells frame the occupation beginning around 8,500 years ago.

At that time, sea levels and shorelines were similar to today, so any arrival required real seafaring, not a land bridge or tidal trick.

That matters for how we picture final hunter gatherers in the central Mediterranean. They were not pinned to big mainlands, they were mobile, organized, and willing to cross beyond the horizon.

How a 62-mile crossing was possible

“Optimistically, this crossing would have taken place at a speed of 2-3 km per hour, and would have required periods of rest. A 100 km crossing would therefore require several hours of darkness even during the longest day of the year,” said Prof. Nicholas Vella of the University of Malta.

Ocean measurements in the Maltese Channel show surface flows commonly around 0.41 to 0.53 meters per second, roughly 0.9 to 1.2 miles per hour, with shifts during strong wind events that could help or hinder paddlers.

Canoe trials with replica dugouts in the Aegean reached paddling speeds up to about 5.5 km per hour, around 3.4 miles per hour, showing what a skilled crew could sustain in fair conditions.

Across the world, long before farmers, people planned and executed sea journeys to reach island lands.

Modeling of Ice Age movements into Sahul argues for intentional, organized voyages rather than accidental drifts, a useful comparison for the discipline even if the settings differ.

What Latnija reveals about daily life

The Latnija layers include hearths, ash beds, and thousands of cooked gastropods along with crabs, sea urchins, fish, and a seal bone, all pointing to an island diet built from both shore and sea.

Alongside that menu were wild land animals, including red deer remains with burning. Stone flakes in local limestone show a practical toolkit rather than ornate microliths.

Later Neolithic communities in Malta ate very differently.

Stable isotope measurements on human bone from the Brochtorff Circle indicate diets dominated by terrestrial foods from crops and livestock rather than seafood, which underscores how distinctive the Mesolithic pattern is at Latnija.

Tools and fire layers at Latnija

Excavations at Latnija mapped a thick ash horizon with in situ hearths, thermal alteration of sediments, and beds of tip-lined shells. Those details make the case for repeated cooking, not a single visit.

The lithic assemblage, 64 pieces from the Mesolithic levels, centers on simple flakes struck from limestone pebbles. The spare technology fits a small, mobile population working with what the island provided.

Charcoal and plant microremains add more texture. Phytoliths and anthracology show shrubs like lentisk used as fuel, while wild seeds appear charred in hearth deposits.

Latnija changes human prehistory

The discovery rejects an old assumption that small, remote Mediterranean islands were empty until farmers with better boats showed up.

Here, late Holocene hunter gatherers reached one of the region’s most isolated archipelagos at least a thousand years earlier than expected.

It also raises questions about island ecosystems shaped by people before the farming era. Some endemic animals vanished on Malta and nearby islands, and early visits may be part of that story.

“Our discovery connects Malta with a much deeper human prehistory, it roots Malta to the story of humanity itself,” added Prof. Scerri.

Archaeology’s task now is to trace the networks implied by an open-sea hop of this size. One crossing suggests more routes, more signals, and more contact than the standard picture allows.

The study is published in Nature.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–