Very rare baby pterosaur fossils tell the sad story of how they died 150 million years ago

Science often works like a detective story, piecing together fragments of the past. Fossils provide some of the most important clues, but they rarely tell the whole story.

Now, two tiny fossils from Solnhofen are rewriting a mystery that puzzled paleontologists for decades. Researchers at the University of Leicester have revealed how baby pterosaurs met their end 150 million years ago.

Fragile baby pterosaurs

The findings, published in Current Biology, show that powerful storms not only killed these fragile creatures but also preserved them in remarkable detail.

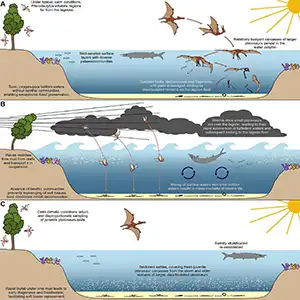

Storm-driven waves and rapid burial in fine mud created the perfect conditions for fossilization. This helps explain why hundreds of small pterosaurs appear in the fossil record, while their larger relatives remain scarce.

The Mesozoic era is often remembered for its giants: massive dinosaurs, predatory marine reptiles, and wide-winged pterosaurs.

Yet most ecosystems, then and now, were filled with small animals.

Fossilization tends to highlight the giants, leaving smaller creatures hidden. On rare occasions, conditions flip the script, capturing delicate life forms in extraordinary clarity.

Famous baby pterosaur fossils

Southern Germany’s Solnhofen Limestones hold one of the world’s most famous fossil collections. These lagoonal deposits are celebrated for preserving everything from insects to pterosaurs in exquisite detail.

Yet one puzzle has stood out. Most pterosaur fossils here are small, young individuals, preserved whole. Larger adults appear rarely, and usually as fragments.

“Pterosaurs had incredibly lightweight skeletons. Hollow, thin-walled bones are ideal for flight but terrible for fossilization. The odds of preserving one are already slim and finding a fossil that tells you how the animal died is even rarer,” noted lead author Rab Smyth from the University of Leicester.

The discovery of two baby pterosaurs provided the missing link. Nicknamed Lucky and Lucky II, these hatchlings had wingspans of under 20 centimeters (8 inches).

Their skeletons are intact, but each shows the same clean fracture on a wing bone. Such injuries point to violent gusts rather than collisions with hard surfaces.

Struggles of baby pterosaurs

Storm winds likely twisted their wings mid-flight. Injured and unable to fly, the hatchlings fell into lagoon waters, where storm-driven waves drowned them.

Fine lime mud then buried them quickly, sealing their delicate forms. Their tragic end became a gift to science.

Many other small pterosaurs found at Solnhofen show no trauma but were preserved in the same way. Researchers now believe baby pterosaurs were especially vulnerable to sudden storms.

Tossed into lagoons, they drowned and settled into the mud. This explains the abundance of juveniles in the fossil record.

Larger adults, stronger fliers, survived the storms but decomposed differently, leaving only scattered remains.

Storms and fossil bias

The new study adds weight to this view. It suggests that storm activity played a major role in shaping the fossil record, selectively capturing the most fragile members of pterosaur populations, the babies.

These conditions favored rapid burial and articulation, explaining why juvenile fossils appear unusually complete.

Adults, that were less likely to perish directly in storms, decomposed in open water, which reduced their preservation potential.

“For centuries, scientists believed that the Solnhofen lagoon ecosystems were dominated by small pterosaurs,” Smyth noted.

“But we now know this view is deeply biased. Many of these pterosaurs weren’t native to the lagoon at all. Most are inexperienced juveniles that were likely living on nearby islands and that were unfortunately caught up in powerful storms.”

Autopsy after 150 million years

“When Rab spotted Lucky we were very excited but realized that it was a one-off. Was it representative in any way? A year later, when Rab noticed Lucky II we knew that it was no longer a freak find but evidence of how these animals were dying,” added co-author David Unwin.

“Later still, when we had a chance to light-up Lucky II with our UV torches, it literally leapt out of the rock at us – and our hearts stopped. Neither of us will ever forget that moment.”

These discoveries change how scientists understand both fossilization and pterosaur life. What once seemed like a world ruled by tiny fliers was in fact a selective snapshot shaped by violent storms.

Lucky and Lucky II reveal not only the fragility of young life but also the power of nature to record its own history.

The study is published in the journal Current Biology.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–